Women can’t park and men don’t listen. Are these just prejudices or are female and male brains actually organized differently? Jülich researchers let artificial ingelligence decide. The answer: it's complicated.

Detailed mapping of the brain began with the discovery of the two language centres for sound articulation and language comprehension by the French anatomist Paul Broca in 1861 and the German neurologist Carl Wernicke in 1874. We now know which areas of the brain allow us to speak, see, hear, move, understand, and feel. And yet, every brain is different in detail.

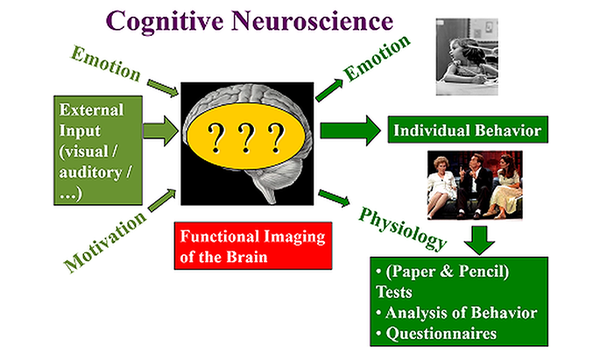

"We are interested in the individual differences in the structural and functional organization of the brain," says Privatdozentin Susanne Weis, head of the Brain Variability group at the Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine (INM-7). A very fundamental difference between individuals is their sex.* Anatomically, it is clearly male or female in most cases. Susanne Weis and her team wanted to know whether these differences are also reflected in the brain and, if so, where.

Each person a colourful mix

In contrast to earlier psychological tests in which women and men competed against each other in the disciplines of spatial thinking, language comprehension, or fine motor skills, the test subjects in the Jülich study did nothing. "We wanted to see what differences there are at rest, detached from any tasks," emphasizes Weis. To do so, the team used artificial intelligence (AI) to analyse over 1,600 MRI images from their own and several large brain studies.

The AI was trained to recognize patterns in 500 functional regions of the brain, classify them as typically male or typically female, and then decide whether the subject was a man or a woman. The success rate was around 70 %. "But why not 100 %?" asks Weis. A closer look at the data revealed that each of the 500 regions tends to fall into the category of male or female – or even both. This results in a colourful mix of male, female, and ambiguous areas for each person. "And that is the case with the majority of the brains tested," underlines Weis. There are, therefore, hardly any purely female or purely male brains. Instead, brains nearly always have either more female, more male, or predominantly ambiguous regions.

More similar in older age

The AI’s success rate was higher in some brain regions than in others: In the regions for emotions, social understanding, spatial memory, and language, the AI discovered clear differences between men and women. So is it a case of being a typical man or a typical woman after all? "Stereotypes don’t come about by chance," Weis stresses, "but the studies show that there is no such thing as the typical male or the typical female brain – we are all somewhere in between." And it has not yet been conclusively clarified where the differences in the brain regions come from: whether they are hereditary, acquired, or shaped by the environment, lifestyle, or experiences, says Weis.

The researchers also discovered a completely surprising result, as the AI identified many more regions in the brains of young people that could be categorized as typically male or typically female. So do the sexes become more and more alike in old age? Intuitively, the researchers had assumed that the differences between men and women would become more pronounced over the course of a lifetime, for example due to social conditioning. One possible interpretation of the new finding: "Each brain becomes slightly less efficient with age. To compensate for this, it has to find other ways of dealing with certain tasks. There appear to be increasingly fewer different possibilities over time, meaning that we become more and more similar," the neuroscientist assumes. However, the researchers want to take another closer look at these data.

"The overlap between the male and female characteristics of the brain is enormous – each brain is a unique mosaic of both."

Susanne Weis

The interpretation of the data is also complicated by the following fact: "The function and organization of the brain is constantly shifting – sometimes within the space of a month," stresses Weis. The hemispheres of a woman’s brain sometimes work together more and sometimes less depending on the phase of a woman’s menstrual cycle. Weis and her colleagues therefore also advocate recording the hormone status of the test subjects in brain studies in order to better understand its effects.

More individual and more tolerant

Since there appears to be a lot of the opposite sex in each of us, Weis believes that mutual tolerance in particular has been strengthened: "The overlap between the male and female characteristics of the brain is enormous – each brain is a unique mosaic of both." She therefore warns against falling into the trap of selective perception: "You might categorize a man who parks badly as an exception and forget about the incident very quickly. Whereas the woman who is a good listener is simply pigeonholed as being a female empath. Gender is one aspect that influences our brain," says Weis, "but it is only one factor. Many other components make us who we are: a unique and typical individual."

* Most brain studies conducted to date have not asked which gender someone feels they belong to. Only the biological sex is recorded. However, INM-7 also conducts research into issues of social gender, such as transgender. Social gender refers to a person’s individual identity and social role in relation to gender.

Text: Brigitte Stahl-Busse | image above: Studio Bachmann - stock.adobe.com

Contact

- Institute of Neurosciences and Medicine (INM)

- Brain and Behaviour (INM-7)