“The term ‘Massenpanik’, or ‘mass panic’ in English, distracts from the real causes” – Interview with Dr. Maik Boltes

29 September 2025

Why do people get into danger at large events – and what goes wrong? Whether at pop concerts, sporting events, or pilgrimages: when people are injured or even killed in crowds, the term “Massenpanik” is often used in German reporting. Literally "mass panic", the phrase is far more established in German than in English. And precisely that, says Dr. Maik Boltes, makes it misleading.

The researcher at Forschungszentrum Jülich has been studying for years how people move in crowds – and under what conditions safety-critical situations arise that can lead to dramatic incidents. He strongly argues against the use of the term "Massenpanik" or “mass panic.” In an interview, he explains why.

Dr. Maik Boltes, what bothers you about the term "Massenpanik" or “mass panic” in English?

What I find critical here are the ideas associated with this term. Many people have experienced situations in dense crowds themselves –so they know the initial situation from their own experience. You can ask yourself what you understand by “mass panic.” What happens in such situations? What led to the accident and who is responsible for it?

The media often use the German term “Massenpanik" when serious accidents occur in crowds, often even resulting in death. The exact circumstances are often not investigated. It is a standard term for this type of accident. The common perception is that the crowd as a whole moves headlessly as a mass and that the people in the crowd behave irrationally and selfishly, which in some cases leads to accidents with fatal consequences. And that is wrong.

This perception – reinforced by the term itself – distracts from the actual causes. By talking about “mass panic,” responsibility is implicitly shifted to the victims, while the role of the organizers, security forces, or authorities is ignored.

What should be taken into account when reporting?

It is usually structural errors that have led to such tragedies. The reason for these accidents is mostly due to excessive crowd density as a result of inadequate organization. For example, the number of visitors or their distribution may have been misjudged, or crowd management or communication on site may not have worked. Or there may have been structural bottlenecks in the pedestrian facilities. As researchers in the field of pedestrian dynamics, we therefore call for the use of unbiased terms such as „Unglück in einer Menschenmenge“ or "accident in a crowd”. If a single term is to be used to describe the phenomenon, it is most likely the term “Massenunglück" or "mass accident", even if the term “mass” suggests collective misconduct, which is usually not the case.

But it is not just a matter of choice of words. It is also important to describe incidents accurately and report objectively on their causes. Only in this way can we learn from mistakes for future large-scale events. Fact-based language helps to better understand the actual causes and support effective safety measures.

So simply replace “Massenpanik” with another term?

Unfortunately, it is not enough at present to simply replace the term “Massenpanik.” Alternative terms are also often mistakenly associated with the image of a panicked crowd. We therefore recommend naming the specific spatial and organizational factors that led to the accident. As long as the stereotypical image remains in people's minds, it is therefore necessary to additionally classify the incident in a descriptive manner.

What does research say on the subject?

People usually act rationally in relation to the situation they find themselves in and are usually even helpful. If someone falls to the ground, people often try to help that person up. Even if this is not always possible due to external conditions. Research shows that people usually act calmly and cooperatively in emergency situations. The stereotypical image of an uncontrolled, panicked crowd ruthlessly trampling each other does not correspond to real observations. In fact, eyewitness accounts and scientific analyses show that helpfulness plays a central role.

Nevertheless, there are limitations. In a crowd, the field of perception is severely restricted, particularly for small people, due to the limited visibility and the prevailing noise level. As a result, the problems of other people in the vicinity are often only noticed at a late stage.

Can you give specific examples?

My colleagues evaluated witness statements from the 2010 Love Parade disaster in Duisburg. The most common reports were of helpful behavior – for example, lifting or passing people along, protecting people lying on the ground, offering encouragement, and distributing water. People helped each other, even at the risk of their own lives.

Surprisingly, active pushing was rarely mentioned, even though the situation was described as “crowded.” At first, some people perceived the crowded situation as normal, as large crowds are to be expected at festivals. Recognition of the danger often came late and was limited to specific areas. Although many witnesses used the term “panic” to express the intensity of their own fear, they rejected the idea of an irrational “mass panic.”

You are researching such accidents using computer models and experiments. What specific lessons can be learned from this?

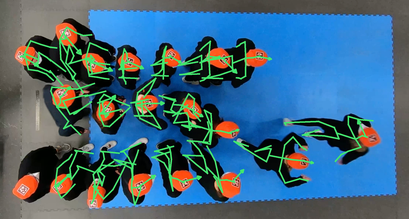

Our analyses help to better understand the occurrence of potentially dangerous densities in crowds: When and where do they occur, and what measures can reduce the likelihood of their occurrence? What are the influencing factors – is it people's motivation, or is it structural conditions such as the width of doors and access points? We investigate how collective movements spread within a dense crowd, when congestion occurs, and what happens when it suddenly dissipates.

As already mentioned, the causes of accidents in crowds are mostly due to excessive crowd density resulting from inadequate organization or structural bottlenecks in pedestrian facilities. When planning large events or transport infrastructure such as train stations, it is therefore important to avoid very dense crowds if possible, or at least to identify and defuse them in good time. To prevent the situation from continuing for too long, pre-planned intervention measures are needed, such as targeted communication, adapted traffic management, or the provision of additional alternative areas. In general, the situation must always remain manageable so that a timely response can be made.

What advice would you give to visitors to future large-scale events?

That's difficult to say. Our recommendations are primarily aimed at event organizers, crowd managers, and security personnel. In addition, at certain events, the atmosphere may encourage participants to stand close together.

As an individual, you have little influence on the organizational conditions that prevent it from becoming too crowded. Therefore, if you expect dense crowds, the only advice is rather simple: wear sturdy shoes, take enough to drink with you, and stay together as a group. In a group, problems are noticed more quickly and people are often more willing to help.

Contact

- Institute for Advanced Simulation (IAS)

- Civil Safety Research (IAS-7)