Computational and Systems Neuroscience

Research at IAS-6 is not an endeavor conducted in single working groups but an interactive effort combining different expertise in one common scientific area - computational neuroscience.

Neuronal circuit models help researchers better understand how nerve cells in the brain work together and can be used computationally to advance brain research. A key step toward computational neuroscience was the model of early sensory cortex developed by Dr. Tobias Potjans and Prof. Markus Diesmann, known as PD14. Published in 2014, it has become a research standard – as a basis for more complex brain models, as a testbed for computational methods, and as a benchmark for the performance of new computer systems.

In April 2024, researchers from around the world met at the Käte Hamburger Center for Advanced Study in the Humanities “Cultures of Research” at RWTH Aachen University to reflect on the model’s importance for work in computational and theoretical neuroscience on the occasion of its tenth anniversary. The results of the symposium have now been published in the journal Cerebral Cortex. In this interview, Prof. Markus Diesmann and Prof. Hans Ekkehard Plesser, lead author of the report, discuss the significance of PD14 and the opportunities and challenges of digital neuroscience, as illustrated for example by the European research platform EBRAINS.

Diesmann: We originally developed PD14 to better understand how the structure of neuronal networks affects their activity patterns. Over the past ten years, PD14 has inspired many lines of research. Researchers have used it as a building block for larger brain models, as a reference model for theoretical analyses, and as a benchmark for novel neuromorphic computer systems. This was made possible by systematic support for technology projects from the European Union over the last 20 years. Projects such as the Human Brain Project (HBP) have brought neuroscience into the realm of large-scale research and made EBRAINS possible. Within these projects, shared standards for the sharing and documentation of models were established. As a demanding use case, PD14 was selected as a demo already in the EU project BrainScaleS and has since driven further development.

Plesser: Even today, many neuronal models are implemented in general-purpose programming languages such as MATLAB, Python, or C. This often limits their potential for reuse. Nevertheless, in the ten years since PD14 was published, neuroscience has made great progress in scientific software development. Research code is now created according to modern software-engineering principles, and the new field of Research Software Engineering (RSE) is gaining international importance. While hardware is usually replaced about every five years, scientific software such as the NEURON or NEST simulators remains relevant for decades. As a result, scientific software must be seen, operated, and funded as a permanent research infrastructure – a point that funding bodies have so far only partly addressed.

Plesser: Large initiatives such as the Human Brain Project have changed how the community thinks. Models and simulation systems are now treated separately: simulation codes are provided as stable infrastructure, while researchers can investigate very different networks on the same platform. Open repositories such as OSB, ModelDB, or the EBRAINS Knowledge Graph make these models accessible worldwide, and standardized model description languages such as PyNN and NeuroML ensure compatibility.

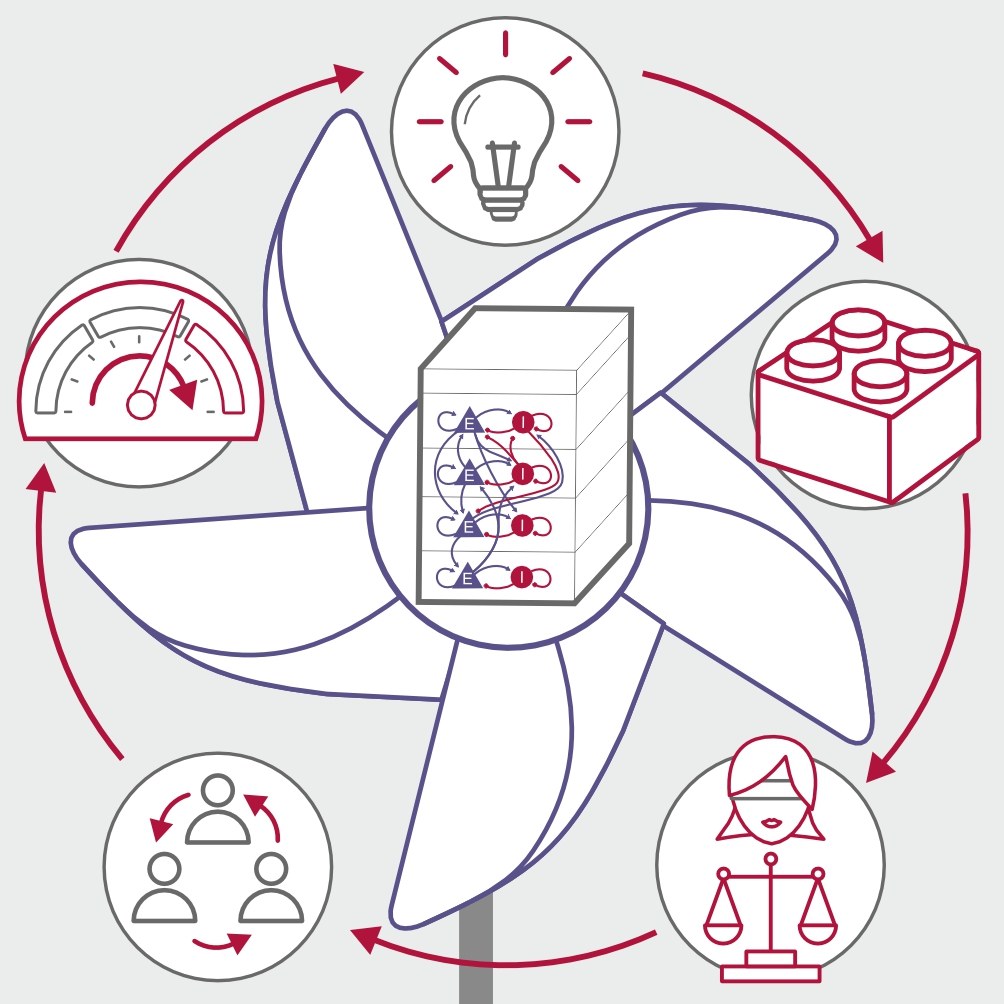

The model of the cortical microcircuit (center) had an impact on five aspects of research (clockwise from top): conceived to provide neuroscience insight, the model became a building block of more advanced models, served as reference for the validation of mean-field theories, drove the development of methods for model sharing, and became a standard for benchmarking of neuromorphic and GPU systems.

Diesmann: The experimental data basis for large-scale models has improved significantly thanks to techniques such as 3D electron microscopy, high-resolution electrophysiology, optophysiology, and layer-specific MRI. Projects like MICrONS provide standardized datasets that make it easier to construct data-driven models. These new datasets enable the validation and further development of the PD14 model, especially with regard to network dynamics and functional tests. PD14 already serves as a blueprint for building new, larger brain models that are composed from existing building blocks. The model helps define standards for the exchange and reuse of models and promotes collaboration between computer science, physics, biology, and engineering.

Diesmann: Future models will increasingly represent realistic, spatially organized structures and closed functional circuits of the brain. After all, the brain does not exist just to produce neural activity but to enable rapid information processing for the organism. The original PD14 model did not yet include function – but that is what we are working on now. This brings the vision of so-called digital twins of the brain closer: virtual counterparts of biological systems that allow experiments and hypothesis testing in silico. In contrast to today’s AI, the focus here is on uncovering the mechanisms of information processing in the brain. These insights, in turn, can inform future AI systems. Conversely, AI already supports this progress by learning complex relationships from large datasets and predicting neuronal responses.

Plesser: Many models are still developed individually and in an ad hoc manner, often without integrating existing infrastructures – as self-written code on a laptop. Sometimes we even hear: “Everything I care about I can do on my laptop.” But a new generation of researchers, shaped by international training programs and cloud-based model platforms like EBRAINS, is working more collaboratively and using shared tools as a common foundation. This development may mark a turning point at which neuroscience evolves from a discipline of individual pioneers into a collaborative large-scale enterprise.

About PD14

The PD14 model describes the connectivity of about 77,000 nerve cells with around 300 million synaptic connections under an area of only one square millimetre of cortical surface. It consists of fewer than 400 lines of Python code and can even be simulated on modern laptops. In the spirit of open and transparent science (FAIR principles: findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable), the model has been released in several variants. One of these is based on the PyNN language and has been made available to the research community via the Open Source Brain platform. PD14 has been very successful: by March 2024 it had been used as a component in 52 scientific studies and cited in over 230 publications.

Original publication: Hans Ekkehard Plesser, Andrew P Davison, Markus Diesmann, Tomoki Fukai, Tobias Gemmeke, Padraig Gleeson, James C Knight, Thomas Nowotny, Alexandre René, Oliver Rhodes, Antonio C Roque, Johanna Senk, Tilo Schwalger, Tim Stadtmann, Gianmarco Tiddia, Sacha J van Albada, Building on models—a perspective for computational neuroscience, Cerebral Cortex, Volume 35, Issue 11, November 2025, bhaf295, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf295

Guest Scientist

Director of IAS-6/ INM-10 Group Leader - Computational Neurophysics

Director of the INM-1 and Working Group Leader "Architecture and Brain Function"